Collaboration Helps Patients Who Have Genetic Epilepsies

Since the first gene for epilepsy was discovered, an additional 75 epilepsy-causing genes have been identified, leading to more precise diagnoses and, in some cases, new therapies.

The rapid progress means today’s patients with a genetic diagnosis for their epilepsy need the support of neurologists and geneticists with expertise in the field’s latest developments. That expertise is now available at the new Translational Medicine Clinic for the Genetic Epilepsies at CUIMC—a collaboration between the precision medicine epilepsy research programs of the Institute for Genomic Medicine and Columbia’s Comprehensive Epilepsy Center.

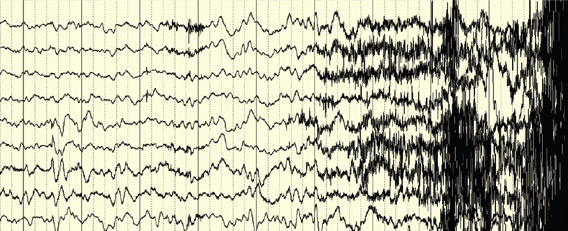

Until the past decade, patients who suffered from epilepsy were categorized into groups based on seizure severity and EEG patterns, even though patients within the same category may have had entirely different underlying causes for their epilepsy.

“We are only now able to diagnose epilepsy properly,” says Tristan Sands, MD, PhD, assistant professor of neurology and an epileptologist specializing in genetic epilepsies. “We are able to diagnose patients on the basis of their genetic differences, which gets to the heart of why they have epilepsy and opens the door for precision medicine approaches to target the underlying problem.”

Patients who arrive at the clinic bring their most recent genetic test results for interpretation. During the visit, patients are seen by Dr. Sands and the clinic’s genetic counselor, Michelle Ernst. After studying the patient’s genetic test results, the team provides a detailed personalized report of the patient’s particular genetic epilepsy with the most accurate information about the relationship between the genetic findings to the patient’s epilepsy and genetic variant.

In some cases, Dr. Sands says, understanding a patient’s genetic test results can lead to important treatment modifications. Some treatments have been identified for patients with specific genes, and other diagnoses may indicate that certain drugs should be avoided or that epilepsy surgery may be warranted.

For patients whose treatment is not modified, “we want to give them a better understanding about the conditions seen in people with similar variations in this gene,” says Ms. Ernst, “and how we expect those conditions to impact a person’s life.” The team also provides patients and family members with information about the hereditary nature of the genetic finding and reproductive risks.

“Many patients with epilepsy are getting genetic testing, but often the results are not conclusive,” adds Dr. Sands. “The testing may have identified a ‘variant of uncertain significance,’ and it is not clear if that truly explains their epilepsy.”

These patients are encouraged to return periodically, often once a year, so the team, which keeps abreast of the medical literature, can update patients with any new information about their particular genetic epilepsy.

Dr. Sands and Ms. Ernst also provide patients with information about emerging precision medicine trials and research opportunities applicable to their epilepsy and refer them to support networks and advocacy groups.

There are many epilepsies and for every gene associated with epilepsy, there are many variants, says Dr. Sands.

To schedule an appointment with the Translational Medicine Clinic for the Genetic Epilepsies, contact Jeffrey Nunez at 212-342-6867.

- Log in to post comments