New York Brain Bank

Beneath NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, tucked within a labyrinthine network of corridors, is the New York Brain Bank, a key research resource for the study of neurodegeneration.

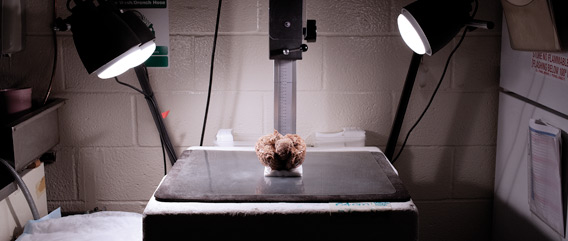

In 10 massive freezers, the New York Brain Bank houses the meticulously catalogued brains of more than 5,000 donors with neurodegenerative diseases. Banking of frozen autopsy brains for research is not new and over the years has improved to allow the preservation of the tissue to be suitable for today’s cellular and genetic analyses. When Jean Paul Vonsattel, MD, became director of the neuropathology core of Columbia’s NIH-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, he introduced a method of preserving the dissected brain tissue in liquid nitrogen vapor following a uniform sampling protocol. The precision with which brains are dissected, studied, and stored has made possible all kinds of research in neurodegenerative disorders and attracted visits from teams of scientists and doctors from around the world.

The precision with which brains are dissected, studied, and stored makes possible all kinds of research in neurodegenerative disorders.

Dr. Vonsattel, director of the brain bank, professor of pathology & cell biology, and attending pathologist at the Columbia University Medical Center, is known for his studies on the pathology of Huntington’s disease. Born and trained in Switzerland, Dr. Vonsattel moved to Boston in the late ’70s to work with esteemed neuropathologist Edward Richardson, director of Massachusetts General Hospital’s neuropathology laboratory. The two eventually joined Edward Bird, who established what is now known as the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center. It was from this fruitful partnership at Harvard that Dr. Vonsattel learned much of what he brought to Columbia in 2001.

Speedy Withdrawals

This is how the brain bank works: A researcher goes to the brain bank, which is linked to a custom-built database that contains the clinical and pathological information on every brain in the bank. The researcher finds the needed tissue—say, a piece of cerebellum with Parkinson’s—and requests the tissue. The request comes with a set of coordinates that direct a technician at the brain bank to a particular freezer, which has numbered shelves, racks, columns, and boxes—which are further divided into numbered rows and columns. It is here, in either a small plastic bag or vial color-coded to indicate the part of the brain from which it came, that the requested tissue can be found. It takes only a few minutes to retrieve, and the average time between request and disbursal is about five business days. The freezers are currently at 98 percent capacity, and not an inch of space is wasted.

“It’s like Wal-Mart meets a brain bank,” says John Crary, MD, PhD, assistant professor of pathology & cell biology. “If you want a piece of the hippocampus, it’s already there and ready to go. The beauty is that you put a lot of work in upfront, so when it comes out, it comes out fast.”

Since neurodegenerative diseases affect the brain in roughly symmetrical fashion—i.e., one half mimics the other—a fresh brain is cut down the middle. One half is cut into slices and “fixed” in formalin, a method that goes back hundreds of years. The other half is carefully divided into “blocks”—or particular regions of the brain—and frozen using liquid nitrogen vapor. A single brain yields as many as 150 blocks for freezing.

The brain bank’s method allows for a single brain to be used in many different ways. Fixed tissue is excellent for teaching, so it is used to instruct medical residents at NewYork-Presbyterian, with which the brain bank shares staff and equipment. Dr. Vonsattel and the bank’s assistant director, Etty Cortés, MD, also use the fixed tissue to make a detailed pathological examination of the brain, the results of which determine how the fresh samples will be classified in the computer and filed in the freezer. The unfixed, fresh tissue is used in biochemistry and molecular biology research. A small portion of the brain is also pulverized and mixed with liquid nitrogen for use in chemical and molecular studies.

“The idea was to make a system to be used beyond the university,” says Dr. Vonsattel. “This is customized for us and though it’s now copied in Munich and Japan, it’s still a work in progress.”

Researchers worldwide rely on the bank’s extensive collection of dissected and catalogued brain tissue for their work in neurodegenerative diseases. The bank works closely with other brain banks, each of which has its own focus—e.g., pediatrics, autism.

Many of the day-to-day duties in the bank fall to Dr. Cortés, who holds the keys to the freezers. She handles requests from researchers for samples—300 a month, on average. She is on call 24 hours a day, should a fresh brain arrive.

“As you can see, there are no windows here,” Dr. Cortés says. “You couldn’t stay here if you don’t like this. For us, this is a passion.” Born in Colombia to a family of physicians, including neurologists, she trained in surgical pathology at the Industrial University of Santander, where in 1999 she earned her medical degree. In 2006, after completing her residency, she moved to the United States to work as a postdoctoral research scientist on Dr. Vonsattel’s team. Dr. Cortés spent three months observing before she could handle fixed tissue. After six months, she could handle fresh tissue, and at nine months she was able to process a brain on her own.

The Process Begins Before Death

The moment a donor dies, the brain tissue so precious to researchers starts to decompose. The sooner the brain is put on ice, the better. But goals of science must be brought into accord with the family’s right to grieve.

Carol Moskowitz, autopsy coordinator at the brain bank until her retirement in September, is mindful of that balance. As autopsy coordinator since 1995, she was the person who received the call from the next of kin when the donor died.

To talk about one’s own death is scary. To consider donating a piece of one’s body—especially the brain, the epicenter of personality—is to acknowledge mortality in an uncomfortably tangible way. And the decision is not only the donor’s to make: The entire family is involved, for the survivors must take responsibility for carrying out their loved one’s wish.

Donors and their families are encouraged to participate because the brain they donate might contribute to a treatment that could spare future generations some of the pain the donor suffered. It might even help lead to a cure.

More information about the New York Brain Bank, which is affiliated with Columbia’s Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Aging Brain, can be found at its website, http://nybb.hs.columbia.edu, or the Taub site, http://cumc.columbia.edu/dept/taub.

Part of her job was to work with the donor to draft a plan detailing the course of action that would be followed when the donor died. She would find a nearby pathologist who could remove the brain, and the donor would pick a funeral home. Since each state makes its own rules regulating organ donation, Ms. Moskowitz would rely on the funeral homes to provide information about local laws.

The next of kin was instructed to call Ms. Moskowitz as soon as possible after death. But real life does not always adhere to a plan. “People are in chaos,” she says of the next of kin. “The person they’ve been married to for 50 years just died, and now they’re calling this perfect stranger.”

Her role in that moment was both teacher and counselor. She had to tactfully explain the process of donation, to the degree that the person wanted to hear, while offering a sympathetic ear. “I’d start by asking, ‘Are you all alone, or do you have family there with you?’ The family dynamic is really important, because if the donor made all these plans and didn’t tell anybody else, there’s a lot of teaching going on.”

For the next few hours her role was to be part of the family, privy to its private world. “I would ask them, ‘Is there something you’re waiting for—are there children coming to say goodbye to their dad?” Ms. Moskowitz says. “‘Do you need to say goodbye? Is there something you wished to do, and you feel like you’re being pushed because you had to make this call?’ I would tell them that at Columbia, care comes first and research comes second.”

In each case, Ms. Moskowitz confirmed the family’s intent to donate the brain because the donor’s wishes are not legally binding. Families say yes almost every time, Ms. Moskowitz says. Some want to know exactly what will become of their loved one, step by step, so she described the process: On its way to the funeral home, the body is brought to an autopsy suite, where the local pathologist extracts the brain from a small, triangle-shaped hole in the back of the skull. The brain is then placed on ice in a bucket sent by Columbia. Within hours, a courier service arrives to pick up and personally deliver the brain to the New York Brain Bank, where it is received by either Dr. Vonsattel or Dr. Cortés.

“They’re stunned,” Ms. Moskowitz says of the families. “‘You don’t send it FedEx?’ No! It’s handed person to person. No one throws the box anywhere. They’re very impressed. They see that this is the gift of life.”

Once the brain arrives at the brain bank, it undergoes a pathology evaluation to definitively determine what condition afflicted the donor. Sometimes the pathology results do not match the clinical evidence gathered while the patient was alive. A person may have appeared to have Parkinson’s, for instance, but the pathology evaluation does not confirm that. For this reason, Ms. Moskowitz often would follow up with the family to share the final findings. This is more than a matter of courtesy: Since neurodegenerative diseases are thought to have a genetic component, it is important that the family be informed.

Priceless Gift

Spread out on the desk in Dr. Vonsattel’s office are dozens of glass slides stained using Luxol fast blue and Hematoxylin and eosin, as well as other dyes, to highlight particular proteins.

Researchers worldwide rely on the New York Brain Bank’s extensive collection of dissected and catalogued brain tissue for their work in neurodegenerative diseases.

“Come, sit,” he says, motioning toward a big, antique-looking microscope designed so that two people can sit opposite each another and look at a sample at the same time. “Have you used one of these before?”

He places a slide under the microscope and gestures toward the viewfinder: The view is of a beautiful wash of blue and purple and red, freckled with black dots. The tissue is from the brain of a person who had Alzheimer’s disease. With a palpable sense of wonder, Dr. Vonsattel describes the pathological features of the disease, highlighting the amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles that the German physician Alois Alzheimer first described in 1906. Research into the causes of Alzheimer’s is more exigent than ever as people live longer, increasing their likelihood of developing the disease.

The New York Brain Bank makes this work possible. But first, it asks people with Alzheimer’s—or Parkinson’s or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or Huntington’s disease, or any number of other dementias and movement disorders—to make the call that offers a priceless gift: their brain.

“They’re amazing people, letting us go into their brain,” Dr. Vonsattel says. “Those people are with us, each of them, even though they are dead. For me, it’s religious. These people are amazing.”

- Log in to post comments