Women—Long Denied a Role at P&S—Helped Shape Medicine in the 20th Century

The College of Physicians and Surgeons, an independent New York medical school that opened in 1807, merged with Columbia’s medical faculty in 1814 before entering into a limited partnership with Columbia in 1860. In 1891, when Columbia and P&S had fully merged, a newspaper article described the merger and its benefits for faculty (“A large amount of money will be spent in the encouragement of original research”) and for students (“the opportunities given to the students for advanced study will be greater than have ever before been offered in New York”). Columbia’s president was quoted as saying the merger put the college in a position that “will make it the best medical college in America, if not in the world.” One stipulation of the 1891 merger was not reported—that the medical school would retain “the right to refuse instruction to women.” It would be another quarter of a century before that changed.

In October 1917, 12 women—10 percent of the entering class—became the first female students. Chief among them was Gulli Lindh Muller’21, who later became one of the first female interns at Presbyterian Hospital and briefly worked as an instructor at P&S before following her husband to New England.

Perhaps the college’s most famous luminaries for the better part of the 20th century were two Virginias: Virginia Kneeland Frantz’22 and Virginia Apgar’33. A surgical pathologist, Dr. Frantz was a renowned teacher, author, and researcher who served on the P&S faculty from 1924 to 1964. Second in her class of 74 students, Dr. Frantz was the first woman named to a surgical internship at Presbyterian Hospital. In 1949, Dr. Apgar, an anesthesiologist, became the first woman to be appointed to a full professorship at P&S. She gained renown for her Apgar newborn scoring system.

These women are legendary among P&S history enthusiasts. Presented here are profiles of just a few of the other women who made contributions to P&S history while serving on the faculty during the 20th century; they, too, shaped the course of P&S—and medical—history.

First In Class

Hattie E. Alexander, MD, 1901-1968

Bacteriologist Hattie E. Alexander, MD, started her P&S career as an intern at Presbyterian Hospital in 1931. She remained a vital presence at the college throughout the next four decades and by the time she earned the rank of professor emeritus of pediatrics in 1966, achieving first-in-class status had become second nature to the Baltimore native.

As an assistant professor of pediatrics in 1939, Dr. Alexander developed the first effective treatment for meningitis caused by Hemophilus influenza, turning pediatric bacterial meningitis from a certain death sentence into a condition with an 80 percent recovery rate. In 1961, Dr. Alexander was the first female recipient of the American Therapeutic Society’s Oscar B. Hunter Memorial Award. Three years later, she became the first woman elected president of the American Pediatric Society.

Today, pediatricians have a wealth of antibiotic drugs available to treat newborns diagnosed with bacterial meningitis. Dr. Alexander’s development, an H. influenzae anti-serum prepared in inoculated rabbits, saved thousands of lives in the years before sulfa-based drugs—and later, antibiotics like penicillin—rendered the anti-serum obsolete. “Beginning with the great impact of the sulfa drugs in 1936,” she told the New York Times, “and continuing with the emergence of the antibiotics in the 1940s, progress controlling children’s diseases was almost indescribably dramatic. There is no more dramatic story in all of medicine.”

As signs emerged that overuse could weaken the effect of antibiotics, Dr. Alexander and her research associate, Grace Leidy, demonstrated the role of genetic mutation in antibiotic resistance and turned their attention to analyses of DNA in H. influenza and, later, polio, tuberculosis, and other infectious diseases. Throughout her career, Dr. Alexander was a leading authority on the treatment of bacterial meningitis, integrating her work in theoretical biology with active clinical service and teaching duties. She also directed the bacteriology laboratory at Babies Hospital. Dr. Alexander published 20 textbooks and more than 100 peer-reviewed papers and helped to found the journal Pediatric Research.

“It was Hattie’s hope that the results of her studies on the inheritance of genetic traits in microorganisms might prove applicable to the understanding of traits in human cells,” wrote Carpentier Professor of Pediatrics Edward J. Curnen, MD, in Dr. Alexander’s obituary. “Creative scientist, compassionate physician, perceptive teacher, and lovely lady, she was ever a seeker of truth—tough minded and gentle, inquisitive, industrious, kind, determined, even stubbornly tenacious, intolerant of bluff or compromise, loyal, devoted, and helpful to the causes and people she believed in.”

Identification of Cystic Fibrosis

Dorothy H. Andersen, MD, PhD, 1901-1963

After she was denied a surgical residency at the University of Rochester due to her sex, Dorothy H. Andersen, MD, decamped to P&S, where she joined the staff in the Department of Pathology. From 1929 to 1935, she served as an instructor of pathology, conducted basic research into the endocrine glands and mechanisms of female reproduction, and earned a PhD.

Dr. Andersen also conducted research that provided a foundation for open-heart surgery at Presbyterian Hospital; recognized cystic fibrosis as a unique disease and developed the first tests for its diagnosis; and investigated glycogen storage diseases. Over the course of her career, she authored or co-authored close to 100 papers.

Dr. Andersen “in great measure had two characteristics that seem self-contradictory: a powerful drive for hard, steady work and extraordinary flexibility,” wrote Nicholas Christy’51, in a “Faculty Remembered” profile (Spring/Summer 2004 P&S Journal). “In her long research career she successfully reinvented herself two or three times without stumbling, without interrupting the progress of her investigative work.”

Dr. Andersen began her rise through the ranks at Babies Hospital in 1935, where she held posts as pathologist and pediatrician for the next 28 years, with faculty appointments at P&S. Immediately on her arrival at Babies, she embarked on an exhaustive study of congenital heart anomalies. Her series of lectures on the topic for cardiovascular surgeons and specialists in pediatric cardiology proved important for the development of open-heart surgery.

Simultaneously, Dr. Andersen became intrigued by the digestive tract. A 1938 paper, “Cystic fibrosis of pancreas and its relation to celiac disease; clinical and pathological study,” garnered great renown and sparked a quarter century of research. “Trained neither as a chemist nor as a clinical pediatrician, she met the demands of her cystic fibrosis work by training herself along these lines and in the course of time became an able clinician, always with a sense of humility and an awareness of her limitations, though the awareness usually exceeded the limitations,” recalled Douglas S. Damrosch’40 in an obituary for the Journal of Pediatrics.

In addition to conducting research, Dr. Andersen carried a large clinical load at Babies, maintained a full teaching schedule, and organized regular conferences on clinical pathology. It was in her approach to the workload that Dr. Andersen’s childhood in the Green Mountains was perhaps most evident, recalled Dr. Damrosch, whose own career at Babies began with his residency in 1941. “The only complaints heard from her were the sort of dry, laconic remarks you would expect from a Vermont farmer contemplating the amount of granite to be removed from a potential pasture.”

An accomplished carpenter and stonemason, expert with saw and scythe, Dr. Andersen found weekend respite on her farm in New Jersey’s Kittatinny Mountain range, where she regularly hosted colleagues and young house officers from the hospital. “My guests find some of the entertainment strenuous, for they have shared in building the fireplace, the kitchen chimney, and in doing carpentry and other manual labor around the place,” Dr. Andersen wrote in an undated manuscript. “It is also a good place for sketching, photography, birds, flowers, cooking, eating, and conversation.”

Matriarch of Medical Mycology

Margarita Silva-Hutner, PhD, 1915-2002

In the natural world, fungal growth fuels decomposition, speeding the cycle of nutrients back into the soil. Given their affinity for heat and humidity, fungi play a particularly vital role in tropical and subtropical ecosystems. Within the human body, however, they can wreak havoc; fungal infections precipitate an array of conditions from the relatively benign diaper rash and athlete’s foot to such fatal afflictions as valley fever and meningitis.

Margarita Silva was just 9 years old when the first laboratory of medical mycology in the United States was established at Columbia in 1926. The scientific field was in its infancy and physicians had little to offer by way of diagnosis, let alone treatment, but in the Puerto Rico of Ms. Silva’s childhood, the debilitating and disfiguring consequences of fungal infections would have been readily apparent.

Ms. Silva was a freshly minted, 19-year-old graduate of the University of Puerto Rico when she landed a job as a technologist in the mycology lab of Columbia’s School of Tropical Medicine in San Juan. For the next 13 years, Ms. Silva and her mentor, Arturo L. Carrión, MD, would devote much of their research to chromoblastomycosis, a condition that still runs rampant in Puerto Rico. A subdermal fungal infection introduced by a contaminated thorn or splinter, the condition is characterized by painless but refractory lesions that erupt years after the initial injury.

At Dr. Carrión’s urging, Ms. Silva accepted a scholarship and in 1950, at the age of 35, began graduate studies in plant pathology at Harvard. Later that same year, Ms. Silva joined the P&S Laboratory of Mycology as a researcher and completed her dissertation, “Studies on the Biology of the Fungi of Chromoblastomycosis,” commuting between Manhattan and Boston. In 1952 she joined the dermatology faculty at P&S and in 1956, a newly married Dr. Silva-Hutner became director of the Laboratory of Mycology.

From 1956 until many years after her 1981 retirement, Dr. Silva-Hutner taught a 12-week course that introduced generations of P&S students to general mycology and the fundamentals of fungal structures, as well as the particulars of medical mycology.

Dr. Silva-Hutner’s career spanned the discovery of the first antifungal drug approved for use in humans and an explosion of research into the opportunistic fungal infections that afflict people with compromised immune function, including those with HIV/AIDS. She published more than 50 articles on the taxonomy and biology of pathogenic fungi and her findings helped lay the groundwork for the 1950 discovery of nystatin, the first true antifungal agent.

A Quiet, But Telling, Example

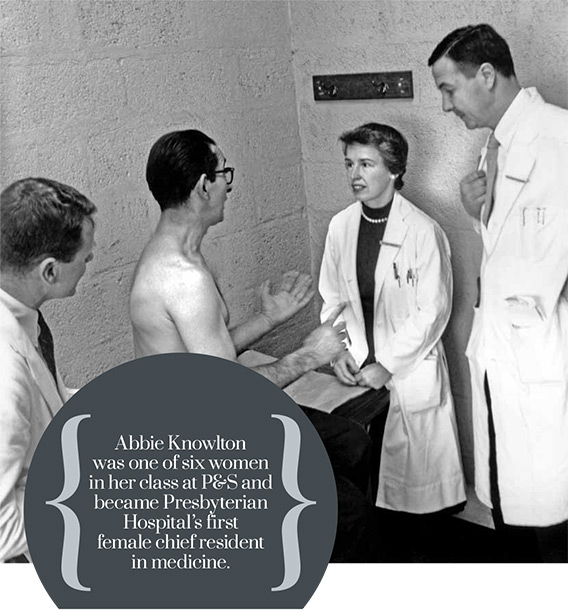

Esther Abbie Ingalls Knowlton, MD, 1918-1997

Abbie Ingalls Knowlton’42 devoted more than a half century to the institution where she completed medical school and began her training. “Dr. Knowlton served as an incomparable role model for all those fortunate to be associated with her,” wrote her P&S colleagues in an obituary in the New York Times. “Wise, vigilant, faithful, and tender in her care of patients, she taught by quiet but telling example what it is to be a physician and friend.”

A nationally and internationally recognized expert in the management of Addison’s disease, Dr. Knowlton authored dozens of papers early in her career that contributed to a basic understanding of adrenal gland physiology. Her contributions to the field were formally recognized in her election to membership in the American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Dr. Knowlton’s research spanned renal insufficiency, the pituitary adrenal axis, the role of aldosterone in normal physiology, and the role of the kidney and renin in normal blood pressure control. Her clinical studies of Addison’s disease in diabetes presaged the trajectory of research and discovery related to the role of autoimmunity in endocrine disorders and her scientific contributions to internal medicine reflect the evolution of the understanding of adrenal, pituitary, and renal physiology. “One of her early papers on Cushing’s disease published in the American Journal of Medicine is a classical paper which is as valid today as when it was first published,” wrote a SUNY Downstate professor in a 1971 letter endorsing Dr. Knowlton’s promotion to associate clinical professor of medicine.

As a teen, Dr. Knowlton shadowed the family doctor on his rounds through the rural resort community of Hot Springs, Va., where she was raised. “The basic business of the physician is the one-to-one relationship with the patient,” she told a reporter in 1996. “No government regulation or HMO constraints can change that.”

As one of six women admitted to P&S in 1938, Dr. Knowlton excelled in her studies and on rounds. “One of the best students that I ever taught—hard worker, full of information, and able to use her facts,” scribbled one professor in his report on her third-year rotation in surgery. Declared another, “This girl’s attitude is certainly brilliant in many ways and she catches the points fast and securely and doesn’t have to be told twice.” In June 1942, Dr. Knowlton embarked on her training at Presbyterian Hospital and in 1945 was named the hospital’s first female chief resident in medicine.

Dr. Knowlton was hired by the medical school as an instructor in 1947 and rose through the ranks to clinical professor of medicine; at the time of her death, she was professor emeritus of medicine.

A Heart for Harlem

Elizabeth Bishop Davis, MD, 1920-2010

Elizabeth Bishop Davis’49 was a first-year medical student at P&S in 1946 when she began the work that would launch her career commitment to providing psychiatric services for the people of Harlem: serving as a clerk at the first mental health clinic in Harlem. Conceived by novelist Richard Wright and psychotherapist Fredric Wertham, MD, the LaFargue Clinic was housed in the basement of the 134th Street parish house of St. Philip’s Protestant Episcopal Church, where the future doctor’s father, civil rights activist Shelton Hale Bishop, and his father before him served as rector.

At the clinic, which operated two evenings each week, volunteer psychiatrists and social workers counseled the working class, predominantly African-American clients. Those who could afford the fee paid 25 cents per session; for those of more limited means, services were free.

After graduation from P&S, Dr. Davis, who received glowing assessments from the faculty, interned at Harlem Hospital and completed her residency at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia’s Psychoanalytic Clinic. In 1953 she was hired as a therapist at Harlem’s Northside Center for Child Development, founded by civil rights activists Kenneth and Mamie Clark, Columbia University’s first PhD graduates in psychology. In 1955, Dr. Davis gained her certification as a psychoanalyst from Columbia’s Center for Psychoanalytic Training and Research. Throughout the 1950s, she maintained a private practice, while continuing her association with an outpatient clinic at Harlem Hospital. In 1957, she joined Columbia’s clinical faculty.

In the early 1960s, New York City hospitals commissioner Ray Trussell began forging relationships between municipal hospitals and private medical schools. P&S was paired with Harlem Hospital and in 1962, Dr. Davis was appointed founding director of Harlem Hospital’s new Department of Psychiatry and assistant professor of clinical psychiatry. A decade later, when she was considered for tenure, Dr. Davis’ colleagues echoed the assessments she had earned from P&S teachers 25 years earlier. “Under her initiative and guidance this service has become one of the outstanding service, teaching, and training centers in the city, able to recruit and retain high caliber staff and to develop innovative service and training programs,” wrote Alexander Thomas, MD, director of Bellevue’s psychiatric division.

By the time Dr. Davis retired in 1978 and became professor emeritus of clinical psychiatry, the Harlem Hospital’s Department of Psychiatry had grown to include an adult inpatient unit, a day hospital, a greatly expanded outpatient clinic with specialty clinics for alcohol and substance abuse, a geriatric clinic, a large social and vocational rehabilitation service, a children’s service with inpatient beds, a children’s day hospital with a public school and recreation program, and a fully accredited psychiatric residency training program.

- Log in to post comments