The First 60-Plus Days at the Epicenter of COVID-19

Tomoaki Kato, MD, is known for performing surgery no other surgeon typically attempts. Recruited to Columbia and NewYork-Presbyterian in 2008, he has performed hundreds of liver transplants in adults and children and so-called ex vivo surgery, in which he takes organs out of the body, cuts the tumor, and puts the organs back. The operations typically take hours, and as a marathon runner, Dr. Kato excels in these marathon surgical procedures.

His surgical prowess took backstage on May 4, though, when he arrived in a wheelchair to a Department of Surgery concert at NYP and joined the performers in singing “A Whole New World.” Still hospitalized from COVID-19 at the time, Dr. Kato explained that he was on a ventilator for a few weeks and ECMO for another few days. “Thanks to my colleagues and thanks to God, I was able to survive.”

Dr. Kato is just one of many COVID-19 patients who have been treated throughout the NYP hospital system. The Columbia and Cornell campuses were the busiest among the 10-hospital NYP system.

In the 60-day period from March 2—when NYP/Columbia admitted its first COVID-19 patient—through April, the number of COVID-19 cases throughout the large NYP system grew daily until hitting the top of the curve on April 13. From then until mid-May, the number of COVID-19 patients hospitalized at the Columbia campus dropped by about 60%. Hospitals throughout the tri-state area saw similar declines.

Columbia and the hospital take pride in their extraordinary response to the crisis that VP&S Dean Lee Goldman, MD, called “the most challenging health crisis of our lives.” The medical school’s response touched all parts of an academic medical center’s mission: teaching, research, and patient care. In addition, VP&S implemented programs to ensure the wellness and mental health of faculty and staff working on the front lines of patient care as well as those working remotely to support the ongoing response.

Each of those missions was fully engaged by the time COVID-19 appeared at the medical center in early March. Below are just a few examples of the response as of early May.

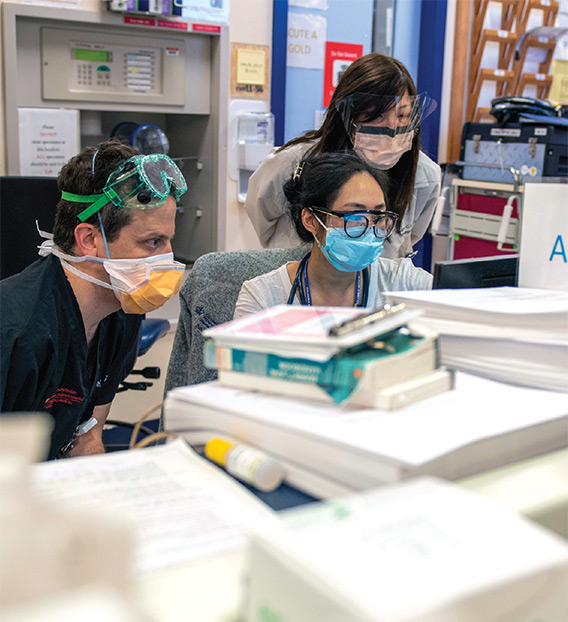

CLINICAL RESPONSE

Planning for the Columbia and NYP response began in January, and by February, protocols were in place in clinical practices to ask patients with fever and lower respiratory illness about their travel history. Patients who had traveled to China, Iran, Italy, or South Korea or had been exposed to someone with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 within the previous two to three weeks were isolated and separated from other patients, and staff interacting with those patients took appropriate precautions based on guidance from NYP Infection Prevention and Control and the New York City health department. By March 5, travel history had become less important in screening patients, as the number of COVID-19 patients in New York City—the epicenter of the U.S. spread of the virus—changed every hour.

About 1,200 clinical staff were redeployed to work in departments other than their own. This included surgeons and ophthalmologists working in the emergency department and internists working in ICUs.

Elective surgery and procedures were deferred and most outpatient ambulatory care was deferred by the time New York City ordered all nonessential workers to stay at home or work remotely on March 22. Deferral of routine or nonurgent care allowed NYP to manage the surge of cases by focusing resources—people, supplies, and space—on emergent care, particularly patients with COVID-19.

Closing most outpatient offices prompted an increase in telemedicine, and ColumbiaDoctors offered training to facilitate the use of remote visits. At one point, more than 50% of ColumbiaDoctors visits—and 60% of prenatal visits—were done virtually.

By March 20, New York City had more than 40% of the nation’s COVID-19 cases. NYP increased its capacity by doubling the number of ICU beds, including creating an 80-bed ICU in an operating suite at NYP/Columbia. This required mapping out the floor plan, changing the wiring in the gas outlets, and making new work spaces. Some hospital space was transformed into a medical/surgical unit, and the conference center at Milstein Heart Hospital became a field hospital. Another field hospital was set up at Columbia’s Baker Athletics Complex to accommodate patients recovering from COVID-19.

A new ICU model of care was needed to accommodate the increasing number of patients and their long ICU stays (an average of 14 to 21 days). The new model of care came together within three weeks. The hospital leadership team that described the effort in a New England Journal of Medicine article called the new ICU units surge ICUs—ICU beds outside of a licensed ICU setting. Teams of facilities, biomed, and IT specialists constructed surge ICUs in a cardiac cath lab, operating rooms, and medical-surgical units. Ventilator capacity was increased by using OR anesthesia machines that would provide necessary invasive ventilation. A number of specialized teams were added to the ICUs. Among them were imaging teams for bedside and portable imaging, proning teams of physical therapists trained to help turn patients in units where the technique was not routinely performed, and family support liaisons who updated families unable to be with loved ones in the hospital.

As the number of COVID-19 patients increased, VP&S leadership announced that faculty and staff could be redeployed to other areas of the medical center. About 1,200 clinical staff at Columbia—many now available because of cancelled elective care, deferred procedures, and consolidation of outpatient practices—were redeployed to work in departments other than their own: surgeons in the emergency department, internists in ICUs. Within departments, even more faculty were assigned to new roles. Nonclinical staff were redeployed to assist the clinical mission by transporting patients, distributing scrubs, assembling face shields, and answering calls to the Workforce Health and Safety hotline.

By late March, concern over ventilator supply increased. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced that New York state approved a protocol developed at Columbia and NYP to use one ventilator for two patients with similar ventilation needs. The protocol was shared with other hospitals. The change prompted the Department of Anesthesiology to create a new role, the physician ventilation specialist, to monitor ventilator use and augment the role of respiratory therapist.

COVID-19 survivor Diana Berrent was the first person in New York state to be screened for antibodies that could be used to treat other patients with the disease. Courtesy of Diana Berrent.

COVID-19 survivor Diana Berrent was the first person in New York state to be screened for antibodies that could be used to treat other patients with the disease. Courtesy of Diana Berrent.An April call by the hospital for volunteers—mostly doctors and nurses—drew hundreds of responses. In addition to retired NYP and New York City area medical personnel and reinforcements from temp agencies, health care workers traveled to New York from the University of California at San Francisco, Cleveland Clinic, Intermountain Healthcare in Utah, the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Arkansas Children’s Hospital, and Cayuga Medical Center at Ithaca, New York, among other places. In all, about 250 physicians joined the NYP medical staff, including doctors from peer academic medical centers less affected by COVID-19.

Andrew D. Thomas’99 was among the volunteers. He left Minnesota, where he is a hand surgeon, to volunteer in the NYP/Columbia COVID ICU. While in NYC, he stayed in his old room at Bard Hall (Room 431). In a letter home, he shared what he said to a team he led while volunteering in the ICU: “I tell them something Coach Spencer told me during a Little League practice when I was 11. Baseball is a game of inches. Well, so is ICU care. You win because you back up the throw to third every single time and run out a ground ball every single time. People survive in ICUs because their ET tubes get suctioned on the hour, every single time, heels are kept off mattress so they don’t ulcerate, every single time. Lines are flushed, sheets are changed, pumps declogged, oral hygiene carried out. We are playing a mortal game of inches and if we win, it will be one inch at time.”

COVID-19 diagnostic test results took five to seven days in early March because patients’ swabs were required to be sent to the CDC. That changed when the NYP-CUIMC Clinical Microbiology Laboratory was able to perform the test. By March 16, NYP and CUIMC laboratories were using a rapid test that could return results in as little as four hours, with a test capacity of over 1,000 samples a day in the entire NYP system. By the end of April, the Columbia lab had processed approximately 20,000 diagnostic tests.

Planning for blood tests to look for antibodies began in mid-March, and by early May the Columbia lab was processing upwards of 1,000 serological samples a day with typical turnaround time of approximately 48-72 hours. With additional automation becoming available, the goal in May was a testing turnaround time of less than 24 hours.

On April 7, Angela Mills, MD, chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine, reported that the number of emergency department patients had decreased over the previous few weeks, but the patients arriving were sicker, most with COVID-19. In recognizing the New York Fire Department cheering outside the ED one night, the many food deliveries, thank you signs, and personal protective equipment (PPE) donations, she says, “While this virus has spread around the world, I’ve seen remarkable acts of kindness that, in my opinion, have been spreading far more quickly than COVID-19.”

RESEARCH

In mid-March, Columbia University announced plans to ramp down research to reduce the number of people on all campuses. Research allowed to continue included any research that could be performed remotely, research related to the coronavirus, clinical research that could directly benefit the patients being studied, and the required continuation or winding down of research that would be lost otherwise.

COVID-19 research ramped up quickly, even before the first patient was admitted to NYP/Columbia. In February, four research teams at Columbia University received a $2.1 million grant to mount an aggressive effort to identify potential antiviral drugs and antibodies for use against COVID-19. The Columbia scientists, led by David Ho, MD, founding scientific director of the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center, are collaborating with academic researchers in China.

Dr. Ho is leading an effort to develop monoclonal antibodies, molecules that can bind to the surface of the coronavirus and neutralize the infectivity of the virus. As a first step, antibodies from blood cells of recovered COVID-19 patients are being isolated. These virus-neutralizing antibodies will then be engineered to optimize their potency against the coronavirus.

W. Ian Lipkin, MD, the John Snow Professor of Epidemiology at the Mailman School of Public Health, professor of neurology and of pathology & cell biology at VP&S, and director of Mailman’s Center for Infection and Immunity, leads a research initiative that uses samples of the live virus to develop rapid and reliable tests to diagnose COVID-19 and identify sources of transmission, particularly in individuals with the infection who have mild disease or are asymptomatic. The samples are housed in a Biosafety Level 3 laboratory.

Courtesy of The Department of Radiology

Courtesy of The Department of RadiologyAs of mid-May, more than 250 COVID-19 research projects were underway throughout Columbia University. That includes clinical trials. As New York City became the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, Columbia physicians became some of the first doctors to notice the complications of patients admitted to the hospital. Clinical trials underway at Columbia test different therapies and preventive techniques, including sarilumab and remdesivir for hospitalized patients, and optimal treatments for high degrees of clotting seen in patients. Other trials are of recovered patients to determine long-term effects.

People who have survived COVID-19 may have antibodies in their blood plasma that can help current patients, but reliable antibody tests are needed to identify potential plasma donors. “When it became clear that it would take several months for commercial companies to develop a test for antibodies, we started to develop our own,” says Eldad Hod, MD, associate professor of pathology & cell biology, who is screening COVID-19 survivors to find potential plasma donors.

The ELISA antibody test was initially developed in Dr. Ho’s lab. Postdocs in the basic science laboratories of Filippo Mancia, PhD, and Oliver Clarke, PhD, stepped in to produce the viral proteins needed for clinical use of the test. And dozens of postdocs organized by Columbia Researchers Against COVID worked long shifts into the evening hours to collect hundreds of patient blood samples that were needed to validate the tests.

“These are difficult assays to develop,” Dr. Hod says. “Other substances in blood samples can interfere, and we had to develop quality control agents so testing is the same from day to day. It was 24/7 for a couple of weeks to get this up in the right way.”

By April 14, Columbia’s assay had received approval from the New York State Department of Health and the first tests were processed. By the end of April, the assay had been semi-automated and nearly 500 tests are run each day to measure the prevalence of the disease and screen for convalescent plasma donors.

Other research has been conducted on how the virus affects the heart. In March, two teams of Columbia cardiologists published some of the first U.S.-based reviews about the effect of COVID-19 on the heart. “There were reports coming out of China about nonrespiratory manifestations, and the cardiovascular manifestations were among the most important,” says Sahil Parikh, MD, associate professor of medicine and director of endovascular services in Columbia’s Division of Cardiology, who led one of the reviews about COVID-19 and the heart.

A study published in May that reviewed 28 heart transplant patients diagnosed with COVID-19 showed the fatality rate at 25%. “Recipients of heart transplant are at high risk for severe complications from coronavirus disease 2019 infection; management of this population is complex and should take place in a transplant center,” the authors wrote.

Columbia physicians in other fields, including palliative care, organ transplantation, obstetrics, and neurology, also shared their experiences in journal articles.

Curtailing all but COVID-19 and other essential research allowed researchers to pivot to projects focused on the pandemic. Kenneth Olive, PhD, associate professor of medicine, brought together a team of volunteers—students, postdocs, staff scientists, and administrative staff—to assist with the surging COVID-19 response. More than 700 volunteers signed up and worked more than 1,500 hours at NYP hospitals, helped process more than 20,000 samples in the biorepository, processed nearly 2,000 samples in the precision genomics lab, and assisted in the serology lab.

“It is unprecedented in all of human history to have as abrupt a change in global scientific attention as we’ve had in this very short period of time.”

Clinical trials are testing existing drugs, while other research laboratories look for entirely new compounds that will work against the new coronavirus and coronaviruses that may emerge in the future. “Over the past two decades we’ve seen the emergence of three deadly coronaviruses: SARS, MERS, and now SARS-CoV-2,” says Dr. Ho. “We believe it is likely that new coronaviruses will emerge in the future.”

Columbia researchers learn about each other’s COVID research through a weekly COVID symposium, and a centralized and searchable database of COVID-related activities at Columbia, the Columbia COVID Hub, helps to coordinate efforts and avoid duplication among researchers.

Much of the COVID-related research relies on the efforts of Columbia’s COVID Biobank, which has enrolled almost 800 patients and stored blood and tissue samples collected during their medical care. “When a researcher asks a question like ‘How many patients who had COVID-19 had renal failure?’ our biobank can provide the samples for this cohort,” says Jennifer Williamson, associate vice dean for research policy and scientific strategy at VP&S. “We can help the researcher get access to the data they need.”

David Goldstein, PhD, director of Columbia’s Institute for Genomic Medicine, called the global attention on COVID-19 inspiring. “One thing that I have been really struck by is just how much of the global scientific community has turned its attention to work on this problem. It is unprecedented in all of human history to have as abrupt a change in global scientific attention as we’ve had in this very short period of time. And that is what gives me certainty. I don’t know exactly when—I don’t know if it’s one year, two years, three years—but we are going to be in a dramatically better position in the fight against this virus in a relatively short period of time.”

EDUCATION

By mid-March, all classes throughout Columbia were moved online, including those at VP&S, and medical student clerkships and clinical electives were suspended. Students in Bard Hall were required to move to reduce the density in residential housing, particularly given the hall’s shared bathrooms and showers.

Fourth-year medical students graduated early—on April 15—to give them an opportunity to volunteer at NYP before beginning their residencies. Of the 139 graduates, 88 chose to support the work of front-line workers at NYP.

In addition to attending online classes, medical students at all levels kept busy with service-learning projects. Several joined nursing, dental, and public health students to create the COVID-19 Student Service Corps to lend a virtual hand to the COVID-19 effort through remote service-learning. Students staffed a community information line, created a task force to organize collection of PPE, and volunteered remotely with laboratories engaged in COVID-19 projects. The group also released a toolkit to help other academic medical centers create their own chapters.

Another group of students launched a GoFundMe campaign called “Mask On, March On!” that raised money for PPE. The students delivered more than 10,000 pieces of PPE to several hospitals in COVID-19 hotspots in New York City.

The Musicians’ Guild lent musical support by moving its “Musical Mondays” online. The now weekly concerts feature live and pre-recorded musical pieces performed by students, faculty, and staff. The mission is to deliver musical respite and comfort during the COVID-19 pandemic to the CUIMC community at large, say first-year VP&S students and co-leaders of the Guild Erika Mitsui, Brandon Vilarello, and Huey Shih.

Courtesy of Adedeji Adeniyi'23 For "Mask On, March On!" Campaign

Courtesy of Adedeji Adeniyi'23 For "Mask On, March On!" CampaignVibhu Krishna’21 is founder and creative director of a website and Instagram campaign called Faces of the Frontline to share stories of front-line workers through photos and words of affirmation. Kendall Sarson’22 is art director.

And Sandro Luna’22 created a free posture and activity coach app, called ergo/. “After graduating from Stanford in 2018, I wrote down the idea but put it on hold after moving to New York for med school. With the move to online classes and more people working from home on their personal devices, I brought the idea to life and was able to finish it in addition to helping where I can in supporting our front-line workers.” The app is available on Apple’s App Store.

Plans are underway to return medical students to campus for clinical education as soon as training and clinical sites can assure adequate provisions for teaching, including capacity for didactic teaching, appropriate case mix, adequate PPE, and supervision.

PLANNING FOR RECOVERY

When the number of new cases of COVID-19 started to decline, Columbia, CUIMC, and NYP began planning for recovery of all medical center functions. Columbia’s task force made initial recommendations in May for returning students, faculty, and staff to campuses and resuming research.

The pandemic’s intangible challenges include the mental health effects produced by front-line patient care, remote work, and upended educational routines. To respond, the Department of Psychiatry partnered with ColumbiaDoctors to develop CopeColumbia, which provides resources that include individual counseling sessions, peer support groups, guided meditations, town hall meetings, suggested reading, and other tools for managing stress, fear, and anxiety.

The need for CopeColumbia was underscored in late April when Lorna Breen, MD, assistant professor of emergency medicine since 2004 and site director of the Allen Hospital Emergency Department since 2011, died by suicide. She had treated patients since the beginning of the pandemic. “Protective equipment goes beyond masks, gloves, and gowns to include doing our best to take care of ourselves and those around us,” said Dr. Goldman in announcing her death. “The loss of Dr. Breen should reinforce our collective appreciation for each other, our recognition of the emotional as well as physical toll of this crisis, and the need to take care of ourselves and of one another.”

Several projects are underway to document the response to the pandemic at the medical center and beyond. Researchers at Mailman and VP&S have launched an initiative called the COVID-19 Healthcare Personnel Study to survey tens of thousands of employees on the front lines of care throughout New York state—from doctors and nurses to hospital food service workers—to document the challenges and stresses they have faced and to assess serious and persistent physical or mental health issues. In another study, researchers in the Department of Medical Humanities & Ethics at VP&S will seek to identify respondents who report high levels of moral distress, a response that arises when a person is forced to take actions that challenge or violate core ethical beliefs.

WHAT WE STILL DON’T KNOW

Physicians and researchers agree that much more remains to be learned about COVID-19. With no standard treatment and no vaccine available, front-line medical workers treat the symptoms while learning from their patients. As the pandemic progressed, the list of symptoms grew and doctors discovered new ways the coronavirus attacks the body, from inflammatory reactions to blood clots to kidney failure.

With the course of the disease so unpredictable and so many unanswered questions, clinical trials take on new importance. “We still have a lot of unanswered questions: Should we target the virus or the host response, and should combination approaches be used to target this pathogen? What determines rapidity of disease progression? What is the optimal time to intervene?” says Magdalena Sobieszczyk, MD, associate professor of medicine and chief of infectious diseases, who has been overseeing COVID-19 clinical trials at VP&S.

As New York and Columbia were recording lower numbers of COVID-19 cases, doctors in April were faced with another mystery: children who were admitted with a constellation of symptoms related to—but different from—the COVID-19 disease seen in adults. It opened a new chapter of COVID-19 patient care and research.

Among the unanswered questions in COVID-19: How long will immunity last? Can convalescent plasma effectively and safely treat the disease? Can convalescent plasma be used to prevent the disease? Do the nature and intensity of immune responses correspond to how sick people were? How many people were infected but were asymptomatic?

Mitchell Elkind, MD, professor of neurology, told the Washington Post, “The virus can attack a lot of different parts of the body, and we don’t understand why it causes some problems for some people, different problems for others—and no problems at all for a large proportion.”

“We don’t know why there are so many disease presentations or what factors determine those different types of disease,” says Angela Rasmussen, PhD, a virologist at Mailman’s Center for Infection and Immunity. “Bottom line, this virus is just so new that there’s a lot we don’t know.”

More information on the Columbia response to COVID-19 can be found online at the Coronavirus Resource Center at www.cuimc.columbia.edu/coronavirus-resource-center.

- Log in to post comments