After 170 years, a Posthumous Degree

By Martha T. Moore

In New York before the Civil War, African-American doctors were few, and medical education was closed to non-whites. The first black American university-trained doctor, James McCune Smith, went to Scotland to earn his MD before returning to New York in 1837. But more than a decade before slavery ended, David McDonogh, an African-American who was born an enslaved person, was practicing medicine and even specializing, in ophthalmology. Educated at what is now VP&S, he was the first black Columbia-trained doctor in New York.

Born in Louisiana enslaved by the owner of a cotton and sugar plantation, Dr. McDonogh studied at VP&S as part of efforts by the 19th century American Colonization Society’s movement to send African-Americans freed from slavery to Liberia, the African colony founded as a destination for freed African-Americans. But Dr. McDonogh, at the end of his training at Columbia in 1847, did not emigrate, and Columbia did not award him an MD degree.

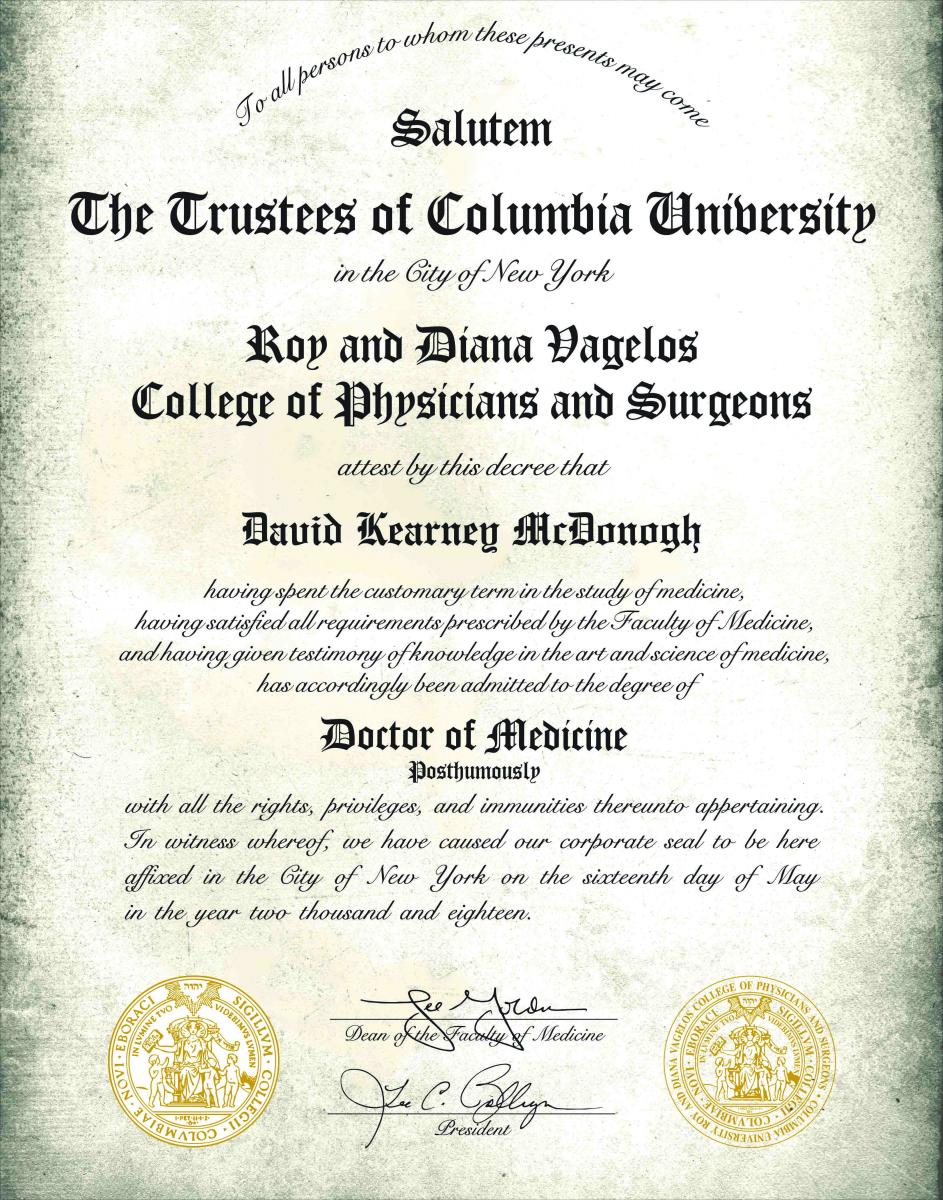

Until this year.

At the 2018 VP&S graduation, Dean Lee Goldman awarded Dr. McDonogh the MD degree he would have received more than 170 years ago had he not been African-American. Dr. Goldman handed the posthumous degree to Patricia Worthy, Dr. McDonogh’s great-great-granddaughter.

“Dr. McDonogh’s qualification for the MD degree has not changed, but Columbia has,” Dr. Goldman said. “Part of celebrating our 250-year anniversary in 2017 included taking stock of our history. During this process, we decided to take action that was unthinkable in the 1800s but completely embraced by our current values.”

When he arrived at Columbia, Dr. McDonogh had already made history as the first African-American graduate of Lafayette College in Easton, Pa. He had been sent to Lafayette by his owner, John McDonogh, a supporter of the American Colonization Society. The colonization movement sought to gradually end slavery in the United States by “repatriating” African-Americans to Liberia, then a colony in Africa founded by the ACS in 1820. David McDonogh was to be educated in preparation for emigration.

When he arrived at Columbia, Dr. McDonogh had already made history as the first African-American graduate of Lafayette College in Easton, Pa. He had been sent to Lafayette by his owner, John McDonogh, a supporter of the American Colonization Society. The colonization movement sought to gradually end slavery in the United States by “repatriating” African-Americans to Liberia, then a colony in Africa founded by the ACS in 1820. David McDonogh was to be educated in preparation for emigration.

David McDonogh was emancipated by his Presbyterian guardian soon after arriving at Lafayette in 1838. By the time he graduated in 1844, he was determined to pursue medical studies despite the whites-only admission policies then in place, and he was “decidedly, utterly and radically opposed”—as he wrote at the time—to going to Liberia before he finished medical training.

McDonogh spent a year training with a physician in Easton and then came to New York. According to an 1895 newspaper account, McDonogh studied at VP&S under John Kearney Rodgers, a prominent faculty member who was a founder of New York Eye and Ear Infirmary. After his time at Columbia, Dr. Rodgers appointed Dr. McDonogh to a staff position at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary. McDonogh adopted the middle name “Kearney” in apparent tribute to his mentor. Throughout his life, Dr. McDonogh identified himself as a VP&S graduate, even though VP&S did not formally recognize his education.

Perhaps not surprisingly, information about McDonogh at Columbia is hard to come by. “Business relating to African-Americans is often not recorded in official records,” says Stephen Novak, head of archives and special collections at the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library. Although three African-American students came to VP&S through the colonization society, “Our records are completely silent on this. If it wasn’t documented in the ACS records at the Library of Congress, we’d have no idea it ever happened.”

Columbia’s medical school did not officially admit a black student until the 20th century, but the first official African-American graduate—Travis J.A. Johnson, Class of 1908—is indicative of how small the New York community of African-American physicians was: Dr. Johnson was the son of a doctor mentored by Dr. McDonogh.

Writing in P&S Journal (now Columbia Medicine) in 2000, the late historian Russell Irvine documented three African-Americans who studied medicine at Columbia before the Civil War with the financial support of the colonization movement. John Brown, a freeman from Connecticut who completed medical studies in 1832 but received no degree, also declined to go to Liberia. He became a teacher and lecturer. Washington Davis, the son of emigres to Liberia, began studies at VP&S in 1832 and returned to Liberia to practice medicine.

Of the three, only Dr. McDonogh worked as a physician in New York, maintaining offices in the heart of the city’s black community as it moved from Greenwich Village to Hell’s Kitchen. Though he trained in ophthalmology, he maintained a general medical practice that included delivering babies.

Raised in bondage, Dr. McDonogh was active in the abolitionist movement. “I can’t say he was best friends with Frederick Douglass but I can put them in the same room,” says Christine McKay, an archivist who researched McDonogh’s life for Lafayette College.

Beginning in 1853, McDonogh was a delegate to “colored conventions,” state and national political meetings that drew leading abolitionists including Douglass and physician James McCune Smith. After the Civil War, McDonogh was a founder of a local Colored Republican Association and was “among the more notable colored men on the stage,” according to a New York Tribune report, for a debate at the Cooper Institute between the presidential campaigns of Ulysses Grant and Horace Greeley.

Dr. McDonogh died of “congestion of the brain” in 1893 at his home in Newark, N.J.

The obelisk on his grave in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx (the cemetery’s website lists him among the notable individuals buried there) befits his hard-won status as a professional and a man of property. Fifty people attended its unveiling, and in 1898, a group of black physicians opened McDonough Memorial Hospital in his honor. (Historical documents suggest he may have changed the spelling of his name, but his grave spells his name “McDonogh.”)

Columbia’s decision to award Dr. McDonogh’s degree comes at a time when universities founded before the Civil War have acknowledged their part in the history of racial discrimination and their ties to enslavement. A 2017 report by Columbia faculty and students, “Columbia University and Slavery,” details the support by VP&S leadership in the 1800s for colonization and theories on the physical inferiority of African-Americans.

“What our students should take from Dr. McDonogh’s life and history is the celebration and recognition of his courage to support the principles of human dignity, freedom, and rights,” says Anne L. Taylor, MD, vice dean for academic affairs at VP&S.

Dr. McDonogh’s degree is not an honorary one, she notes. “This is really awarding him something that he earned, that he was denied because of his race,” Dr. Taylor says. “What this reflects is the university both acknowledging the good that it did—that there were Columbia professors of good conscience who mentored him and nurtured him through his education—and acknowledging that things were done by less than contemporary standards.”

Patricia Worthy says she knew nothing of her great-great-grandfather’s life and achievements until contacted by Lafayette College officials last year. His years in slavery “are a part of history that’s horrible,” she says, “but he was able to persevere. It does make me feel proud.”

Dr. McDonogh’s name will certainly be known at VP&S now: The medical school has established a $1 million endowed scholarship, the David McDonogh Memorial Scholarship. Preference for the scholarship will be given to students who have overcome adversity or hardship to pursue a medical education. The scholarship was made possible by Roy Vagelos’54 and his wife, Diana, who provided funds to endow the McDonogh Memorial Scholarship in perpetuity. “There is no better way to honor Dr. McDonogh and his legacy,” says Dr. Goldman.

Columbia’s recognition of Dr. McDonogh is welcomed by the history professionals who have worked to bring Dr. McDonogh’s story to light.

“I was just delighted. I think that was a wonderful thing for VP&S to have done. It helps to right the record,” says Diane Windham Shaw, the archivist at Lafayette College who has documented McDonogh’s life. “It’s a wonderful tribute. And a richly deserved one.”

Lafayette has honored McDonogh, its first black graduate, with a commemorative sculpture by the renowned African-American sculptor Melvin Edwards. An African-American alumni networking group is named the McDonogh Network. “This is kind of a moment for recognizing and realizing that our history is more complex than we knew,” Ms. Shaw says. “We’ll all be better served by knowing.”

Lafayette has honored McDonogh, its first black graduate, with a commemorative sculpture by the renowned African-American sculptor Melvin Edwards. An African-American alumni networking group is named the McDonogh Network. “This is kind of a moment for recognizing and realizing that our history is more complex than we knew,” Ms. Shaw says. “We’ll all be better served by knowing.”

“It’s great to have a story of a person to fit into New York history that we didn’t know about before—abolition history, Civil War history, community history, medical history,” says Ms. McKay, the archivist. “This is a person whose name has been known, but now we have filled in so many of the blanks.”

One piece of the McDonogh story remains elusive: a photograph of David Kearney McDonogh. A century and a half ago, as photography grew popular, it was common for people of professional attainment to have portraits made, so it is likely that Dr. McDonogh would have sat for the camera.

“Somewhere in this world,” Ms. McKay says, “there is a photograph.”

- Log in to post comments