Lewis "Bud" Rowland

What Lewis “Bud” Rowland, MD, achieved in neurology would have been impressive for anyone, but it was even more remarkable for a man whose career was almost destroyed by politics.

For 25 years, Dr. Rowland chaired Columbia’s Department of Neurology and maintained it as a leader in the field. He founded two neurological disease centers at Columbia, led the American Neurological Association and the American Academy of Neurology, raised nearly $10 million for Parkinson’s research, edited the field’s leading journal for a decade, and, among his other books, produced six editions of the standard textbook for neurology.

He was hard-working and far-seeing. Dr. Rowland, who died in March at the age of 91, long ago predicted that genetics would come to dominate research into Alzheimer’s and other neurological diseases and advocated for what became translational neuroscience with his founding of Columbia’s centers for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and muscular dystrophy.

“He was so prescient about a lot of these things,” says Richard Mayeux, MD, current chair of the Department of Neurology. As a result, Dr. Rowland was key in moving neurology from a field limited to observation and diagnosis to a specialty that includes treatment. Thanks to Dr. Rowland’s legacy, “the scientific basis of the department today is grounded in genetics and genomics and trying to treat these otherwise untreatable disorders,” adds Dr. Mayeux.

“His influence on neurology was enormous,” says Timothy Pedley, MD, who succeeded Dr. Rowland as chair of the department in 1998. “I would say he was one of the major figures in neurology in the past 50 years.”

But Dr. Rowland’s illustrious career was almost over before it started because of the McCarthy era blacklists.

Quietly Refusing to Name Names

In 1953, newly married and about to be a father, Dr. Rowland went to work at the National Institute of Neurological Disease and Blindness, a forerunner of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Already aware of the hunt for alleged Communist sympathizers in government in McCarthyist Washington, Dr. Rowland and his wife, Esther, discovered the FBI was asking their friends questions. Soon, Dr. Rowland found himself summoned to the security office of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, which oversaw the National Institutes of Health.

Both Bud and Esther Rowland were politically progressive. They had met at a fundraiser for a doctors’ group espousing national health care. As a medical student at Yale, Dr. Rowland was president of the Association of Interns and Medical Students, a medical students’ organization committed to ending racism in health care and establishing a national health care system. AIMS, founded in 1941 and with a membership of about 3,000, had been branded a Communist front by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

When he arrived at HEW, security officers permitted Dr. Rowland to call his wife but not a lawyer.

“I told Esther that I was being interrogated by the political police and I said I wasn’t going to talk to them,” Dr. Rowland recalled in a 2012 oral history. “It was like a scene out of Kafka.”

“Remember Einstein,” his wife told him in the phone call. The physicist had recently spoken out about the fear of communism imperiling freedom of research and teaching.

Dr. Rowland’s suspicious activities included being an usher at a Paul Robeson rally, attending a Marxist discussion group at Yale, and not disclosing his membership in the medical students’ group. He was suspected of subscribing to the leftist publications In Fact (he did) and the Daily Worker (he did not) and he refused to answer FBI questions about other alleged leftists. He was labeled by unnamed accusers “a Communist sympathizer.”

“How does one answer such a charge?” Esther Rowland wrote in her 2015 memoir, “Fellow Traveler.”

Dr. Rowland answered it partly with this statement to HEW: “The obligation of good citizens in a democratic society is to eliminate discrimination and to fight for social justice. This is a demonstration of loyalty, not disloyalty, to the United States.’’

Five months after the interview, Dr. Rowland was fired due to “the interests of national security.” His dismissal from the U.S. Public Health Service was listed as “conditions other than honorable.”

His principled stand cost him more than his job: The Rowlands were living in a government-owned apartment at the NIH with their year-old son; they were given two weeks to clear out. The family, expecting a second child, landed on the sofa at Esther’s mother’s in New York. A month later, a job offer at the University of Pennsylvania was withdrawn due to objections from the trustees.

“I thought I would never work again,” Dr. Rowland recalled.

But, as Esther put it, “There were many courageous people who…quietly condemned (McCarthyism) in their own acts of defiance.” With help from H. Houston Merritt, under whom he had trained at Columbia, Dr. Rowland landed a position at Montefiore Hospital, then affiliated with Columbia. All but six years of the rest of his career—when he chaired neurology at Penn—were spent at Columbia.

Wielding the Red Pen

The man who once thought he might never find work became famous for his productivity. He wrote nearly 500 published articles, two books on motor neuron diseases, and books on neurologic and psychotherapeutic drugs. He edited six editions of “Merritt’s Neurology,” one of the standard texts of the field. He had the generosity of spirit to write a history of the very institution that had blacklisted him; “NINDS at 50” appeared in 2003.

“It was thrilling to see my dad’s curiosity about science and the world around him. Science was an endless mystery, a team sport, and a way to do good in the world,” Andy Rowland, Dr. Rowland’s oldest son, recalled at his memorial service.

Grant proposals written by colleagues and friends went under his red pen. Dr. Mayeux recalled once giving Dr. Rowland a program project grant so hefty “it looked like the New York telephone book.” A few days later he was summoned to Dr. Rowland’s apartment and found his 500-page grant proposal in stacks on the living room floor, edited and reorganized. “And it read better,” Dr. Mayeux says.

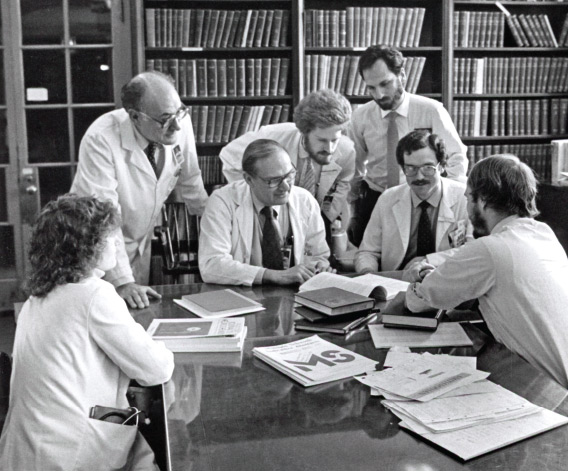

Dr. Rowland, seated at center, at a 1982 meeting

Dr. Rowland, seated at center, at a 1982 meeting“He had a sense of timing, when was it right to be your friend, when was it right to be your colleague, when was it right to be your teacher,” says Dr. Mayeux, who trained under Dr. Rowland. “That was what was unique about him.”

Dr. Rowland edited the journal Neurology from 1977 to 1986 and Neurology Today from 2000 to 2009. “He rewrote every paper that appeared in that journal. Even when (papers) weren’t accepted he would edit them,” Dr. Pedley says. “He told me once, ‘Maybe I’ve gone too far with this. I found myself editing a personal letter from my cousin.’”

That might have been a joke; he was full of jokes and sayings that became known as “Rowlandisms.” He had an endless supply of wisecracks, a red pen and notecards in his shirt pocket, a weakness for Mallomars, and a penchant for catnapping during meetings.

“He had that legendary ability to fall asleep during a conference, usually grand rounds, and then he would wake up when the questions began and he would ask the most important question, which was based on what the speaker had said,” says Howard Hurtig, MD, a friend and colleague during Dr. Rowland’s chairmanship of the neurology department at the University of Pennsylvania. “He was just playing possum.”

Andy, his oldest son, recalls walking through the medical center with his father and watching him pick up bits of paper and trash wherever he spotted them. “He said it was everyone’s job to keep the hospital clean,” recalled the son. “He lived that commitment to public service in large and small ways, whether it was advocating for underserved patient populations or picking up trash.”

Tending Tropical Plants

For a man with a high professional profile, Dr. Rowland knew how to get out of the way, those who knew him say. As a department chair, he worked to make sure the neurologists could pursue what excited them, not him. As a third-year resident, Stanley Fahn, MD, borrowed Dr. Rowland’s lab to work on a project, only to find himself invited to work on a Rowland project and end up co-authoring a paper. It was the start of a long association: Dr. Fahn went with Dr. Rowland to Penn and then returned with him to Columbia in 1973.

“Most places you have to do what the chairman wants,” says Dr. Fahn. “Bud Rowland was never that way. He was an encourager, he wanted people to do what they wanted to do.”

Dr. Rowland treated Columbia’s neurologists like tropical plants, jokes Dr. Mayeux. “He’d give us water and light and get out of the way.”

Or, as Dr. Rowland himself put it in a 2012 interview: “I think the most important thing is to pick good people and then leave them alone. When I’m an editor I try to help people say what they want to say. When I’m involved with somebody’s training, I want to help them do what they want to do.”

Living his Values

Dr. Rowland always rooted for the underdog, whether in sports or in life. Perhaps it was because he knew what it was like to be in the minority. Born in Brooklyn in 1925, he was a Dodgers fan, a high school basketball player, and an aspiring doctor from the moment he set foot in school. As he completed high school, his parents changed the family’s name from Rosenthal to Rowland so their son could avoid restrictions on the number of Jews admitted to Yale. When he returned to Columbia in 1973, he was the first Jewish clinical chair at the university since 1939. Dr. Rowland explored the history of anti-Semitism in academic neurology in his 2009 book on Dr. Tracy Putnam and Dr. Merritt, the two neurologists (and successive department chairs) who in 1938 discovered Dilantin to treat epilepsy. Dr. Rowland documented efforts by Presbyterian Hospital to get Putnam to fire Jewish neurologists on his staff. (Putnam did not, but staffed two neurological services, one with Jewish doctors and one with what Dr. Rowland termed “society” doctors.)

Lewis Rowland and Salvatore DiMauro being interviewed at the 1981 Jerry Lewis MDA Labor Day Telethon

Lewis Rowland and Salvatore DiMauro being interviewed at the 1981 Jerry Lewis MDA Labor Day TelethonWarm and joking, Dr. Rowland was nonetheless strict in his insistence on what was important—precise language—and what was not—a patient’s race or economic status. His trainees learned that patients were to be referred to as men and women, not males and females. They had arms and legs, not extremities. Mentioning their race was irrelevant and so was whether they were being treated by the private or public hospital service. “What, did they have a wallet biopsy or something?” he would ask.

"He was a humanist. He genuinely liked people. There was no such thing as a big shot and a little shot. There were just people, and he helped everybody equally."

As department chair, Dr. Rowland initiated neurology residencies at Harlem Hospital and, rare among department heads, went there himself twice a month to conduct rounds. “Our students and residents got a perspective on medical issues of a disadvantaged inner city population,” Dr. Pedley says, “but they also saw the environment in which those issues occurred and understood a relationship between environment and health care and the consequences of not having the same kind of health care that you have on Park Avenue.”

Influenced by Esther, a dean and preprofessional adviser at Barnard College, Dr. Rowland worked to advance the number of women in neurology. “I think he appointed women where he could both in professional organizations as well as within the department,” says Dr. Pedley. “He had enormous voice nationally about the need for advancing women in neurology and in medicine as a whole.” Today, Columbia’s classes of neurological residents often include more women than men; women make up close to 50 percent of the neurology faculty, including six full professors.

Dr. Rowland’s son, Andy, marvels at his father’s love of talking to people, from the grocery store clerk to whoever he was seated next to at a wedding. However embarrassing it was to teenaged Andy, “for him, it was all about the sharing.”

“He was a humanist. He genuinely liked people. There was no such thing as a big shot and a little shot,” says Dr. Fahn. “There were just people, and he helped everybody equally.”

In a 2000 New York Times article about the wedding of his daughter, Joy, Dr. Rowland proudly pointed out something that indicated his three children were as committed as their parents to serving others. All had chosen careers with an important word in common: public health (Andy), public radio (Steve), and public interest law (Joy). Being Bud Rowland, of course, he closed with a joke: “Which means you don’t get paid.”

- Log in to post comments