David Hosack: Pioneer in Medicine and Doctor at History’s Most Famous Duel

David Hosack was born in 1769 in Manhattan—making this year the 250th anniversary of his birth. He grew up during the British occupation of the island in the Revolutionary War. In this chaotic world, surrounded by blood, disease, and death, Hosack began dreaming of a career devoted to medicine. At the age of 17, he enrolled as an undergraduate at Columbia College. Soon after, he risked his life to defend the anatomical specimens at Columbia and at New York Hospital during the Doctors’ Mob of 1788. Hosack, like a number of other medical students, thought it prudent to leave town for a bit after this unrest, in which at least three people died. The following year he received his BA from the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University). He remained passionately devoted to the progress of medical knowledge the rest of his life, so much so that he would one day conduct an autopsy on his own infant son.

After advanced studies in Philadelphia, Edinburgh, and London, Hosack set up a private practice in New York and joined the Columbia medical faculty with a dual position as professor of materia medicaand botany. Soon Dr. Samuel Bard, a pillar of Columbia and New York medicine who had treated President George Washington, invited Hosack to become the junior partner in his thriving practice. In 1797, Hosack saved the life of Philip Hamilton, the 15-year-old son of Eliza and Alexander Hamilton, earning the young doctor the trust of one of the nation’s most famous and powerful men.

Dr. David Hosack, by John Trumbull, c. 1810, oil on canvas. Used with permission of the Linnean Society of London.

Dr. David Hosack, by John Trumbull, c. 1810, oil on canvas. Used with permission of the Linnean Society of London.Thanks to his pioneering surgeries and his efforts to introduce gentler, more effective treatments to American medicine than the widely used mercury and bloodletting, Hosack quickly became the most sought-after physician in New York and the most famous American physician of his generation. By the time he suffered a stroke in 1835 at the age of 66 after exerting himself during a fire that devastated a vast swath of the city, Hosack had become so famous that newspapers from New Hampshire to South Carolina ran bulletins about his condition and offered prayers for his recovery. Soon after Hosack’s death from that stroke, the American writer Freeman Hunt noted that “[a]s a physician and man of science, his name was universally honoured as the first; as a citizen, his many virtues and excellences of character have made a deep impression upon the hearts of thousands.” Hosack’s death, Hunt wrote, had “left a blank in the scientific and social world.”

What brought David Hosack to the pinnacle of his profession? Here are four defining episodes in a brilliant medical career forged in the tumultuous early years of the nation.

1. “A Difference of Opinion Upon Medical Subjects is Not Incompatible with Medical Friendships”

In 1790, soon after his graduation from Princeton, Hosack moved to Philadelphia to study with Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signatory to the Declaration of Independence and the most famous physician in the United States. Rush’s approach to medicine was iconoclastic, empirical, and restlessly curious, making him the perfect teacher for the inquisitive Hosack. To Hosack’s joy, this eminent American scientist agreed to become his mentor, and Hosack spent hours at Rush’s side—not only in class and in clinical settings but also as a frequent guest at the family dinner table. Hosack memorized his mentor’s personal and professional habits and emulated them for the rest of his life. To maximize time and energy for teaching, medicine, and charity work, Rush arose early, ate sparingly, never touched alcohol, and read late into the night. He loved lively medical debates and encouraged his students to challenge him; Hosack duly criticized Rush’s theories in his 1791 medical thesis on cholera morbus. They would disagree even more publicly on the causes and treatment of yellow fever, even as they sent affectionate letters to each other. “Let us show the world,” Rush wrote Hosack, “that a difference of opinion upon medical subjects is not incompatible with medical friendships; and in so doing, let us throw the whole odium of the hostility of physicians to each other upon their competition for business and money.” Rush called himself Hosack’s “friend and brother in the republic of medicine.” Hosack, in turn, so admired his mentor that, soon after Rush’s death in 1813, he commissioned a portrait of himself seated with a bust of Rush next to him, so that mentor and student looked as though they were continuing their decades-long conversation. Honoring Rush’s example, Hosack soon became a beloved mentor to a new generation of American medical students.

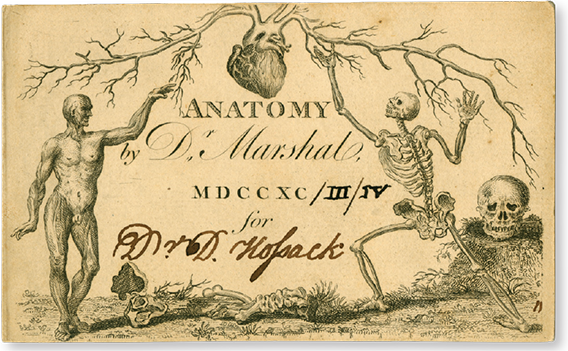

David Hosack’s Admission Card to Dr. Marshal’s Anatomy Course, 1793-94. Archives and Special Collections, Columbia University Health Sciences Library

David Hosack’s Admission Card to Dr. Marshal’s Anatomy Course, 1793-94. Archives and Special Collections, Columbia University Health Sciences Library

2. “Mortified by My Ignorance”: Hosack Discovers Botany

In 1792, Hosack followed in Rush’s footsteps by spending a year in advanced study at the great medical faculty in Edinburgh. Hosack signed up for a punishing regimen, attending classes 12 hours a day. He raced from anatomy to midwifery, from pharmacology to chemistry, from clinical observation to dissection. While in Edinburgh, Hosack discovered what would become his life’s other great passion—botany.

It happened when one of Hosack’s professors invited him on an outing to a botanical garden. As Hosack strolled along listening to the casually erudite conversation around him, he began to panic. Botanical expertise, it seemed, flowed in British veins. Hosack felt, as he later put it, “very much mortified by my ignorance of botany.” He had learned about the importance of plant-based medicines during his American medical studies, but he had thought of them mainly as supplies to be purchased from apothecary shops. Now, in Britain, he suddenly grasped that for doctors and medical professors all across Europe, botanical gardens served as encyclopedias, laboratories, and classrooms all rolled into one. After all, most of the medicines known to doctors came from plants.

Hosack began to think very seriously about trying to found a public American botanical garden devoted to research and teaching and run by the government for the new citizens of a young Republic.

Yet Hosack also learned that no one reallyunderstood just how plant remedies truly worked against particular illnesses—and no one had yet come up with a clear way to discover and isolate newplant-based medicines. Some doctors still subscribed to the so-called Doctrine of Signatures, according to which a medicinal plant was thought to bear the “signature” or symbol of the organ it treated. A plant called lungwort, for example, which has spotted leaves, was thought to resemble lungs and was therefore used to treat lung infections.

Hosack caught fire with a passion to advance medical botany. He moved to London to study for a full year with the greatest British botanists, including Sir Joseph Banks, the famous explorer and president of the Royal Society of London, and James Edward Smith, the president of the Linnean Society of London. When Hosack sailed home in the summer of 1794, he was one of the best-trained botanists in America. In his Columbia lectures, Hosack insisted to his students that the United States deserved doctors just as knowledgeable and skilled as Europe’s, but he found it deeply frustrating that he had no botanical garden to teach them in.

It was around now, in 1797, that Hosack saved Philip Hamilton’s life from a terrible fever. He did so with the help of a medicinal plant: Peruvian bark, made from the cinchona tree, native to the Andes. In the wake of this success, Hosack began to think very seriously about trying to found a botanical garden. He knew of the important garden and nursery of the Bartram family near Philadelphia, founded in 1728 (and still beautifully preserved today). But what Hosack had in mind was a different kind of institution: a public American botanical garden devoted to research and teaching and run by the government for the new citizens of a young Republic.

He lobbied friends, colleagues, and politicians for the money he needed to buy land, build greenhouses, hire gardeners, and collect plants from all over the continent and the world. Many people around him could not grasp what he was trying to do, and some mocked him publicly. They could not see what was apparent to Hosack—that the systematic scientific understanding of the chemicalnature of plants and other remedies was about to emerge as the foundation of modern medicine. This would require a dedicated research facility.

Elgin Botanic Garden

Elgin Botanic GardenAfter several fruitless years of lobbying for funds from Columbia and the state of New York, Hosack began buying up a parcel of 20 acres of Manhattan farmland. It was located on a country lane called the Middle Road, about three miles north of what was then the northern boundary of New York City. Hosack founded the garden at great expense to himself, eventually spending more than a million in today’s dollars on it, all out of his own pocket. He wrote to contacts around the nation and the world pleading for seeds, living plants, and dried specimens—every kind ofplant he could get his hands on. He wanted medicinal plants, of course, but also agricultural, commercially useful, and ornamental plants. Hosack named his garden the Elgin Botanic Garden, after his father’s hometown of Elgin, Scotland. Over the next decade he amassed more than 3,000 species of plants and began training a generation of medical students in pharmacology, medical botany, patient care, and the scientific method.

3. Loss Motivates Him to Specialize in Obstetrics

Hosack’s triumphant rescue of Alexander and Eliza Hamilton’s son Philip in 1797 came on the heels of great personal loss. Hosack’s young wife, Kitty, had died in 1796 during childbirth. The baby had also died—making this the second infant Hosack had lost by the age of 26. His clinical skills had not been enough to save Kitty and the baby. Hosack channeled his helplessness into a professional focus on obstetrics, painting vivid scenes in his Columbia lectures of the overwhelming chaos of childbirth. He told his students that before they entered the delivery room, they must possess complete mental mastery of the birthing process. Once there, they would have “no time for much reflexion much less for consulting books.” He told them it was a matter of life and death that they memorize everything about the reproductive organs—“not merely the soft parts” but also “the structure and configuration of the bones of the pelvis.” He argued that childbirth so fully engaged the whole female body “by means of its membranes, nerves, and blood vessels” that giving birth was “almost one of the vital functions,” like breathing and circulation. He told his students that the physician must radiate confidence both “to yourself” and “to your patient or her friends” because the least uncertainty “manifested by you is observed by them.” They should speak to the mother in a calm, respectful tone while at the same time taking charge.

Hosack believed that every woman, rich or poor, deserved good obstetric care. He began to think about founding a “lying-in” hospital, devoted to helping women give birth safely even if they could not afford to have a doctor making regular house calls. If a doctor’s own wife and baby couldn’t survive childbirth, what was happening in the almshouse, in the boardinghouses, and in all the miserable shacks at the edges of the city? Hosack helped launch a subscription campaign to fund the new hospital, and his friend Alexander Hamilton was among the first subscribers.

Yet there was little Hosack could do for a beloved child when bullets were fired. In 1801, at the age of 19, Philip Hamilton fought a duel to defend his father’s honor. Hosack was at Philip’s bedside with Eliza and Alexander as Philip lay dying of his injuries.

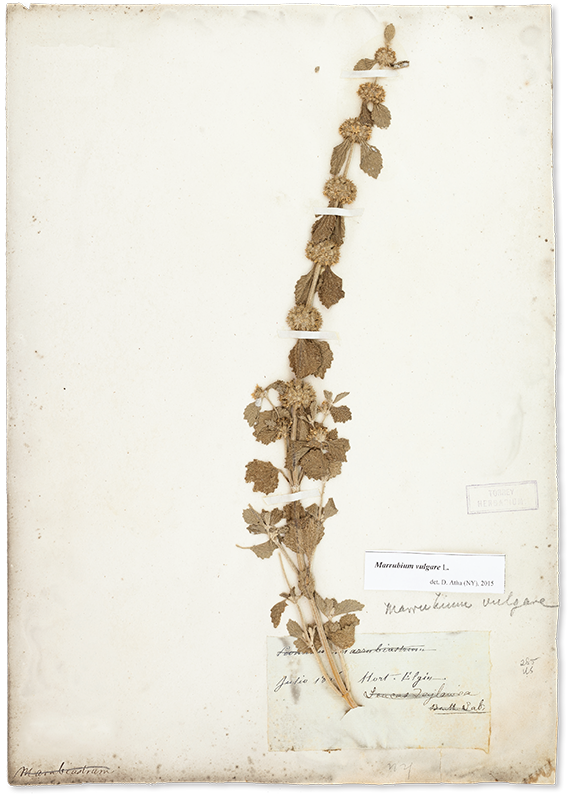

Marrubium vulgare L. (horehound), a medicinal plant collected in 1806 on the grounds of the Elgin Botanic Garden

Marrubium vulgare L. (horehound), a medicinal plant collected in 1806 on the grounds of the Elgin Botanic Garden

4. A Duel Now Known Around the World

By now, Hosack was not only the Hamiltons’ family physician, he was also Aaron Burr’s. In the early summer of 1804, when Hamilton and Burr became embroiled in a war of written words that culminated in Burr challenging Hamilton to a duel, these two bitter foes could agree, at least, on the fact thatHosack was the logical choice to be the attending physician at the duel.

Hosack heard a shot ring out, and then another, and then he heard someone shouting his name. He raced through the underbrush up to the dueling ground, where he saw a sight he would remember until the end of his days.

On July 11, 1804, Hosack stepped into a boat at the edge of the Hudson with Hamilton and Hamilton’s “second” for the duel, a trusted friend named Nathaniel Pendleton who served as Hamilton’s representative in the duel negotiations. When the oarsmen had rowed them to the New Jersey side of the river, Hamilton and Pendleton disappeared into the underbrush to climb to the dueling ground higher up the hillside, where Burr and his second, William P. Van Ness, were waiting. Hosack was left behind on the shore below the dueling ground so he would not be an eyewitness to the duel in the case of legal proceedings.

After a few minutes, Hosack heard a shot ring out, and then another, and then he heard someone shouting his name. He raced through the underbrush up to the dueling ground, where he saw a sight he would remember until the end of his days. Hamilton was lying on the ground, gravely wounded and half-cradled in Pendleton’s arms. Hamilton’s face looked to Hosack like a “countenance of death.” Hosack struggled to keep Hamilton alive as the oarsmen rowed them back to New York City. After a terrible night, Hamilton died at about 2 o’clock on the afternoon of July 12, with Hosack among those at his bedside. Hosack was asked to perform the autopsy on his friend. Tracing the path of Burr’s bullet through Hamilton’s abdomen, Hosack found a mass of clotted blood, and behind that, under his fingers, he could feel Hamilton’s shattered spine.

Hosack was stricken at Hamilton’s death, but he lived by a strict medical principle of staying politically neutral about his patients. Hosack insisted to a friend that “science knows not party politics.” Remarkably, this principle of scientific neutrality allowed him to remain close with Aaron Burr after the duel. When Burr fled to Europe in 1808, after yet more political scandal, Hosack cared for Burr’s beloved daughter, Theodosia, during a terrible illness. Burr died in 1836, nine months after Hosack succumbed to a stroke. In a tidy twist of fate, it fell to one of Hosack’s sons, Dr. Alexander Hosack, to care for Burr in hislast illness.

A Name Forgotten but a Legacy Preserved

David Hosack’s name has largely been forgotten. But his soaring ambitions changed Columbia forever. In 1811, the state of New York purchased Hosack’s pioneering garden from him for the public benefit and renamed it the State Botanic Garden. He had finally realized his dream of a public research institution. Before long, the legislators realized they had no experience in running a botanical garden and turned it over to Columbia College, which prudently held onto the property even as the boundaries of the city moved northward up the island. By the 1870s, Hosack’s former garden was blanketed in apartment buildings and townhouses. In the 1920s, that land, still owned by Columbia, caught the eye of John D. Rockefeller Jr., who had grown up on 54th Street.

Columbia University was by now located uptown on a beautiful McKim, Mead, and White campus, built in part with proceeds from the sale of a parcel of Hosack’s former garden property. Columbia agreed to lease John D. Rockefeller Jr. 11 acres for more than $3 million a year. By the end of the 1930s, he and his partners had built 14 buildings; the tallest one, 30 Rockefeller Plaza, shot 70 stories into the air from Hosack’s former fields of grain. Radio City Music Hall was built over the former footprint of Hosack’s conservatory.

In 1985, Columbia sold its property to the Rockefeller Group for more than $400 million. Hosack’s great creation—the Elgin Botanic Garden—had long since disappeared into oblivion, both physically and in our national memory. But not before he had conducted some of the earliest systematic pharmacological research in the United States and trained the next generation of American medical students, both at the garden and in his wildly popular Columbia courses.

Victoria Johnson is an associate professor of urban policy and planning at Hunter College of the City University of New York. She holds an undergraduate degree from Yale and a doctorate from Columbia. This article is based on her most recent book, “American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic” (Liveright/W.W. Norton, 2018), which was a runner-up for a 2019 Pulitzer Prize, one of five finalists for the 2018 National Book Award in nonfiction, and a New York Times Notable Book of 2018. In addition to her own research for “American Eden,” Dr. Johnson used the following resources for this article: Freeman Hunt’s “Letters about the Hudson River” (1836); Dr. Hosack’s 1791 “Inaugural Dissertation on Cholera Morbus”; letters from Dr. Rush to Dr. Hosack; James Harrar’s “The Story of the Lying-In Hospital of the City of New York” (1938); and Christine Chapman Robbins’ “David Hosack: Citizen of New York” (1964). For more information about David Hosack’s life and work, go to americaneden.org.

- Log in to post comments